With all the high tech apparatus currently being coveted by entertainment programs around the nation it is sometimes easy to forget that many problems can be solved by decidedly low tech, more traditional approaches. In fact, there are several recurring challenges within technical theatre that cry out for easy, kind of "dare to be stupid" solutions. Things like a door in a drop, a low profile wagon, a tall rolling thing that doesn't fall over are all issues that never go away and are never once and for all solved.

I continue to believe that the purpose built solution is one of the coolest things about theatrical technical direction.

Another frequent poser that could be added to the list above is: rolling thing that doesn't roll when its not supposed to. It actually turns out that this particular problem is one that is much easier solved in a high tech environment. A rolling unit on an automation deck with a buried track, driven by a dog on a cable, stops when the cable stops and goes when the cable goes. However, many Technical Directors are faced with this issue on a regular basis working with companies that do not have the resources to implement solutions involving track decks and drive winches. They have to find other ways.

The band-aid solutions to this are usually triangular wedges stuck under the edge, or door stops on the sides, maybe locking casters, or sometimes cane-bolts into holes in the floor. Sometimes you can even find toggle-clamps listed in theatrical supply catalogs as “wagon-brakes.” Most of these work with varying degrees of success. The upside is that they are usually simple and can be added late in the process. The downside is that often the unit doesn’t have a good position for wedging or attaching. Often multiple stops are required to keep the unit from pivoting as well as stopped, and in the case of wedges there are now extra pieces that someone has to remember to remove with the unit. It is possible though to have a much more successful solution to the problem if the device for stopping the unit is designed into the piece from the beginning of fabrication.

A recent project in our shop provided three opportunities to solve this problem in three different ways in one 24 hour period. The different approaches each have advantages and disadvantages, but are all viable, and on the whole are very simple. In two of the cases, the parts for the solution are within the standard inventory of most scene shops.

The first solution came right off the designer's elevation.

For this table piece we were instructed to caster one end of the unit. Wheels on one end, plus doctoring the legs on that end produce a unit that can be lifted like a and pushed on or off stage. When the un-wheeled end is placed on the ground, the unit sits flat and doesn't move.

This was a good solution in this case as the unit travels only out of sight, and because actors will be crawling underneath as part of the stage action; so it was necessary to keep the area underneath as clear as possible. Also, it is about as low tech as one can get. No materials are required for this solution beyond what would have been used to make the unit roll in the first place – in fact, it utilizes less casters in this configuration.

It is worth noting that the framing member supporting the casters gets extra reinforcement at the joints where it joins the legs since it will have to bear most of the weight of the unit on its own. Also notice that this approach uses rigid casters. The wheelbarrow action allows for any path without using pivoting casters. Really, this is a dare to be stupid solution that does everything it needs to do for the production without being complicated.

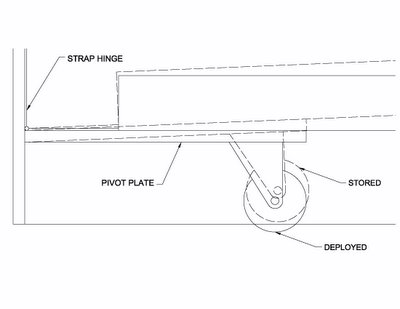

The second approach uses a few moving parts, but is also reasonably simple. This is a fairly classic lift-jack utilizing pivoting casters, strap hinges, a plywood mounting plate, and a long 2x4 lever. Once again, materials that are normally close at hand to any theatrical scene shop.

The wheels for the unit are mounted to the pivoting plates. Each plate is connected to a lever, and the levers are situated such that when one moves it moves the other.

Push the levers down, the plates rock to level pushing the wheels down, and the unit sits up on the wheels to roll away. This particular application utilizes an additional arm with a handle to facilitate operation and locking. In most cases the weight of the unit itself is enough to pivot the jack into the stored position.

This solution was good for this application because there was a good deal of available real-estate within the piece for the mechanism. The scene shift takes place in view of the audience, so once the piece gets its front and side facings this should be reasonably magical. The jack does require a fair amount of space, but with proper planning space can be optimized for other uses of the volume, in this case a shelf for props.

The engaging and disengaging of the mechanism can happen with one stagehand – or even a performer - from a single position. Also the piece only has to carry its own weight so the number of casters and span between the wheels turns out not to be an issue. If the lift jack is actuated from the end of the long lever, the operator gains significant mechanical advantage, so even a unit with some weight to it should not be too unreasonable a challenge to lift, as long as the structure of the mechanism can handle the span introduced.

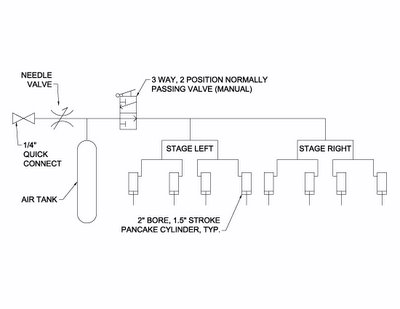

The third iteration is a little more complex. This approach utilizes moving parts, some actuators, and a stored power supply - compressed air.

In this solution, the casters are mounted to a free floating plate contained within the base of the unit. Above the moving plate is a fixed plate, and on that plate there are multiple pneumatic cylinders. A valve is placed between the air supply and the actuators. Apply the air and open the valve, the cylinders extend pushing the unit against the wheels and raising the piece off the floor - free to roll.

Remove the air supply and open the valve and the unit sits back on the floor. The weight of the unit is enough to exhaust the air from the cylinders so the unit is “gravity return.”

In addition to the wheel, plate, and cylinder assembly, this solution requires finding a position to conceal the pressure tank. There also needs to be an accessible place to mount the valve & handle.

This is a good solution for this piece because there is very limited space available. This also works well because this unit actually is a doorway arch, so there are two bases that must lift and there is no way to mechanically link them. Snaking a hose through the header frame to power a second set of cylinders is comparatively simple. Perhaps most interestingly, this solution is completely encased in a unit which does not have an elevation hidden from the audience. When looking at the unit in place, one cannot see any of the mechanics that make the lift possible.

So, three solutions, no wedges, no holes in the deck, no electronics or programming. Just simple machines and a little forethought for three clean solutions.

No comments:

Post a Comment